Problem

Often termed a million-dollar mistake null pointer can be considered a technical detail of implementation. It is, in most cases, in no way related to the business problem we are trying to solve.

You’ve likely encountered — or perhaps even written — snippets like this in countless codebases.

if (wallet) {

wallet.purchase(Present.Bicycle());

}

We can’t really do much with a wallet if we don’t have one — so defensive coding often becomes our last line of defense (pun intended). The downside is that these checks increase the code’s cyclomatic complexity, obscure readability and add noise.

Solution

Fortunately, there is a better alternative. Let’s consider semantics of the previous example in the following way.

Do something if we have a wallet (object). If we don’t, do nothing.

This captures the very essence of the Null Object Pattern.

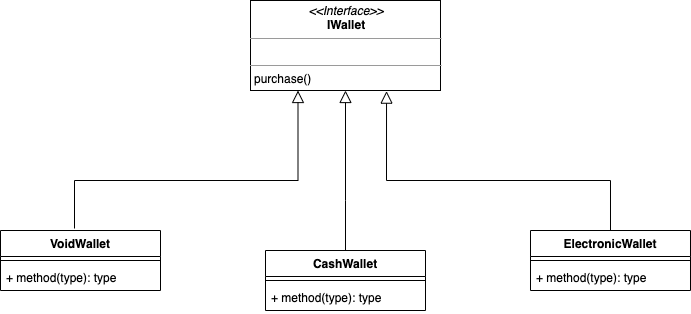

We can define an abstract entity — an interface — that describes the base behavior we expect if the object exists. In our case, that would be IWallet. Such a wallet can have several implementations:

VoidWallet, a no-op implementation ofpurchase(), representing the case when the wallet is missing (wallet == null in the original example).CashWallet, used when payments are made in cash.ElectronicWallet, implementation of electronic payment, such as credit card.

And now the beauty of simplicity. Providing consuming end (client) is supplied with the appropriate runtime

version of the wallet, it only has to do:

wallet.purchase(Present.Bicycle())

Conclusion

The client can completely avoid any null-reference checks. The semantics — whether it’s a void/null wallet or a real wallet — are determined by the runtime type of the object that the wallet reference points to.

This is showcased in this simple github repo. In this repo /src folder mirrors production code. It contains the definition of the IWallet interface along with all its implementations. The test folder demonstrates all the scenarios described above.